Education: Can history teach us tolerance

Comparing German and British education systems regarding teachings about historic ills

It’s the 31st of July 2022. England are playing Germany in the final of the Women’s Euro 2022. As a huge lover of football, I followed the tournament closely, even travelling to watch Germany beat Spain in London. The final is enthralling and England win 2-1 to win the tournament. This is a celebration, however, that would not last long. My phone buzzes and I receive a voice message from the person who I have followed Germany’s progress with, Luca. Born in Germany and a huge football fan, this was a big occasion that she was deeply invested in. I pick up my phone and listen to the voice message and I am met with a very dejected voice which is hushed, coming from the toilet of a pub filled with England fans. Luca says: “There’s been a couple of German bomber songs, theres been a couple of Nazi jokes… I know the drill, I’m sorry, I’m a bit out of it.” These voice notes were followed by messages that some men had threatened to ‘fix her attitude’ and that she was avoiding social media because England fans were posting anti-German content. Luca explains to me that “It’s not going to change”.

That last comment struck a chord. Why can’t this behaviour change and what is the root cause of members of the British public thinking it’s acceptable to equate Luca to those who murdered millions? To fully understand the scale of the problem I wanted to know whether this behaviour was confined purely to football matches, or if it was a greater issue. Luca explains to me that during her first year studying in the United Kingdom and beyond she has been subjected to questions such as

“Why are you here? Why do you speak English? And I was like, well, you know, we have to learn five languages in school.”

The Reichstag in Berlin. Photo courtesy of Luca Wodtke

The Reichstag in Berlin. Photo courtesy of Luca Wodtke

After the United Kingdom, Germany has the most English speakers with 45.8 million people learning the language which is over 50% of the population. Whereas The United Kingdom only has 2.9% of the population that can converse in any other European language. It strikes me that Britain seeks to isolate itself, which could be due to differing educational practices. Luca explains to me that when it came to her education about historic wrongdoings, particularly in an international school where she studied, the atrocities were given context. “So it was quite important to show these people from other countries that, you know, this isn't just what Germany is”. When approaching a similar topic of the second world war, I am intrigued to see how the British curriculum may have altered over the years, and could this have an impact of terms such as Nazi being applied so carelessly to those from Germany? If Britain were to apply practices such as those that are applied in German education to our own historic wrongdoings, would this have a great societal impact of self reflection, or is Britain intent on burying its head in the sand whilst still pointing the fingers at others?

As I take my mind to the education I received in the United Kingdom, I find myself picking at the depth in which some lessons were taught, particularly history. Upon reflection, the topics I studied at school were very much Britain in our ‘glory days’. The Tudors are heavily featured on the schools curriculum and I firmly believe every single person who has experienced the schooling system in Britain can recite what happened to each of Henry the 8ths wives. Would society benefit from more transparent history lessons especially in regards to Britain’s colonial past and would comments like those Luca has faced be lessened by a greater understanding of the historical meaning of words?

Graduating from school a decade ago, I am intrigued by how the schooling system within Britain might have changed, especially with events in recent history causing an outcry for a change of approach towards historic wrongdoings. During the summer of 2020, the Black Lives Matter movement came into focus and rallies were held all around the world. In Bristol in the UK, a statue of Edward Colston, a merchant who invested heavily in the city, was taken down and thrown into Bristol Harbour. This occurred due to Colston being a slave trader, something unknown to many people of the city.

From my own experiences, we only touched upon Britain’s expansive empire in school, and never the methods in which these lands were claimed. This is quite striking considering the British empire had such a large impact both on foreign lands, and shaping Britain as it is today. Were we afraid of our history or did we just not deem it necessary to teach to our youth? Speaking to Louisa McKie, a secondary school teacher in the United Kingdom, she enlightened me to the changes that are being made in the history curriculum: “There has been a big move to decolonise the curriculum, which is sort of since 2020. We are trying to make the curriculum more representative of different groups in history. But trying to blend it in rather than bolt it on”. This is a significant shift in the direction of history lessons at school since I was a student, one that as Louisa stated, was born out of 2020 when there was a real push for educational change. Something that struck me was the application of these lessons. Louisa explained that a ‘bolted on’ style of teaching, where a teacher presents students with facts, would be unhelpful. Instead topics such as slavery are being woven into lessons, coming after teachings of African history. The students are first taught about topics such as the silk road which helps to give an insight into African culture before colonisation, so there can be no misunderstandings that Africa had no history before Europeans stepped foot there.

Louisa contextualises the history she is teaching by relating it to modern day.

“There's a brilliant database that UCL (University College London) have created about compensation from slavery. So I set homework where they use the database to look at how local figures and local buildings have benefitted from the compensation that was paid in slavery, and their minds are blown. They're like, why were they getting money for this?.”

Perhaps the statue of Edward Colston would have been removed earlier, or appropriate signage detailing how he obtained the money he put into Bristol would have been put up, should previous students have been educated in the manner that Louisa is teaching her students. When questioned on whether statues to controversial historical figures should be removed, the students disagreed. “A lot of them are like, no, no, we need to keep it there but use it as an educational tool. Again, having that transparency. They asked why can't we just make it really clear what it was that they were mixed up in and have that as part of the statute being there?”.

Perhaps this is the key, transparency. Some British people, like those who verbally abused Luca, may have benefited from transparent teaching when they were at school. Maybe when confronted by all aspects of Britain’s past, would it hit home that referring to a German as a Nazi is an uninformed, hurtful slur.

This is a problem that could stem from patriotism, something that Britain knows very well, and Germany has shied away from, as my conversation with Eva Maler gave insight to: “If we're talking about the armed forces, for example, or the war in Iraq, language like ‘heroes’, which is something that, as a German, I found that very difficult”. Eva moved to the UK from East Germany when she was 19, and has since set up her own business in the country. I was eager to know more about patriotism within Germany. “I think we can actually mark it up until about 2006, when there was a World Cup in Germany. Up until then, displaying a German flag outside of your house would be very unusual” Eva explains. “I've never seen that anywhere before. In Germany, if you stated the fact that you’re proud to be German, you would almost automatically associate yourself with the far right.”

It seems alien to me, a white British man, that simply displaying a flag of my nation or declaring pride in my country could have political connotations. Whilst Eva assured me things are changing in Germany, especially since the 2006 World Cup, the reluctance to display a German flag up until that point almost certainly has ties to the second world war. I question whether Germany is using the practices that Louisa has started to implement in her classroom, to a further extend than simply being transparent.

“It's done a little bit too much in Germany. So much so that it gives a young person a bit of a guilt complex” Eva tells me. “It's like a collective responsibility, maybe I'm a bit sensitive, but I always thought this is almost like a stain on my personal history. I remember for example, the first time I met somebody who was Jewish, I was in London. I applied to be an au pair for their family. I felt so uncomfortable just talking to this family who were very nice to me and I said ‘do you know i’m German, I'm so sorry’."

The second world war ended nearly 80 years ago and yet Eva alludes to a sense of guilt gained simply by being born German. Something that Louisa wants to avoid in her teaching: “We have to tread very carefully. Because obviously, we have to be completely neutral in terms of our politics and everything as well. But you don't want to be telling them how to feel about what's happened in the past, or making them feel like they ought to be feeling guilty for it and having to apologise.” Louisa clarifies. “But equally, you should come at history at face value of what happened in the past.”

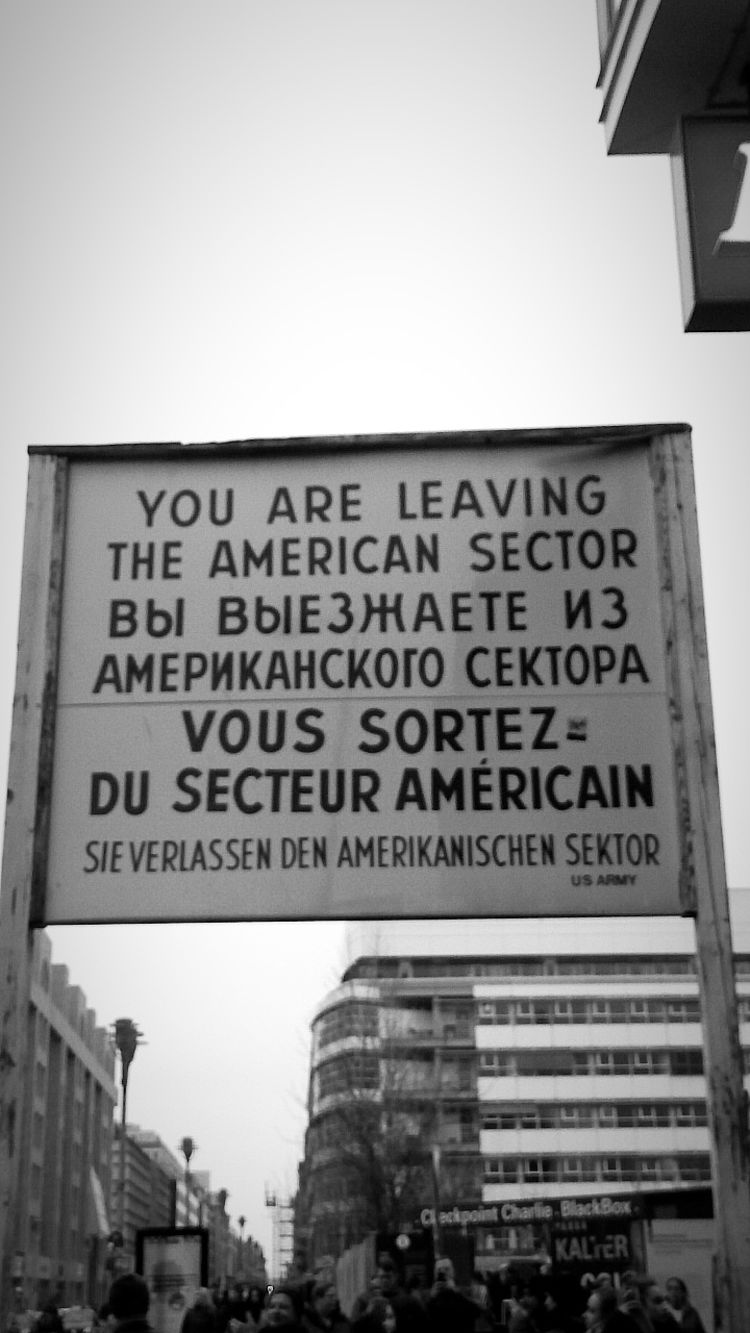

Remnants of a divided Berlin. Photo courtesy of Luca Wodtke

Remnants of a divided Berlin. Photo courtesy of Luca Wodtke

The fine line between educating about historic wrongdoings, and making those from the same nation feel responsible is something that Germany has been tackling for many years. It appears to me, as the education system in the United Kingdom becomes more transparent, that this is an issue teachers will face. But is education in schools enough? For people like Luca, who are forced to shrug off anti-German hatred as part of the norm, should they take the brunt of the abuse and hope the generations that follow will phase out this behaviour? I realise that this problem cannot be wholly changed within a classroom, and societal change would also need to happen.

Creating societal change, as Marianne Christine Dieterich-Greenwood articulated for me: “Big question you have”. Born in 1945 in England to parents who had fled Austria in 1938, Marianne had an upbringing vastly different to the youth of today. Attending a boarding school in England but also experiencing the Italian education system from the age of six, she paints me a picture of an educational establishment unlike the ones today. “My mother told me that the headmaster of my elementary school in Milan was a fascist. I didn't know, I didn't notice anything about it. But we always were marching around the gym, practising marching together in twos or threes”. Marianne highlighted for me that Italy’s hands are not clean when it comes to atrocities in the last century, but they fall to the same practice as the United Kingdom where the glory days of the Roman Empire set the tone in history lessons. Moving to a German school within Italy, Marianne explains to me her education around the Nazi regime: “My teacher presented us an image of a declining Hitler. But he was held up by the public. Because there was so many tiny little people around the Nazis, SS, who were pushing things up or keeping things burning. It was very difficult for many normal German families directly after the war to talk about things that had happened to their Jewish friends. They were still afraid of being out in the open with it. Not realising that there was nobody there anymore to put them in jail or to say you were there as well, you naughty boy. They're all in America, or dead after the Nuremberg Trials.”

This direct approach of education differs with the ‘blend it in’ approach that schools nowadays are implementing. Being born right after the war ended, Marianne has a very different relationship with the topic than the students of today. Her father, Peter Greenwood, was part of the Czech Liberation Army supported by the British, and he was present at D-Day. She is also a once removed cousin of Anne Frank, and has met Otto Frank twice.

“Otto after the war taught tolerance to everybody in schools. Whoever he was meeting he was always saying slow down. Look at each other, not against each other. So well, that's something we were taught without realising where it came from, from my parents.”

Marianne's father Peter Greenwood during WW2. Photo courtesy of Marianne Christine Dieterich-Greenwood

Marianne's father Peter Greenwood during WW2. Photo courtesy of Marianne Christine Dieterich-Greenwood

It was this conversation that I found quite profound. I think of the abuse Luca received for simply being a German supporting the national team, and I wonder whether the teachings of Otto Frank would have benefited those throwing the word ‘Nazi’ around like a plaything. A man who experienced the true horrors of the Nazi regime, who had every right to be angry at the world, decided to teach tolerance. Changing society to be more tolerant cannot happen overnight, but these first hand accounts could impact the older generations and really get them to think about the language they are using. The Nazi’s are those who killed Otto Frank's family, not those who are cheering on the German football team.

When mentioning the rivalry between England and Germany when it comes to football, Marianne chuckles. Having experienced a much harsher education when it came to Nazi Germany, I was intrigued to get her thoughts on the ways in which these words are now used. They are said so easily by the English fans, and yet it rests deeply with those from Germany. “That's a question for the parents. What do parents teach their children nowadays? Do they tell them why these words should not be used instead of saying don't use them?" She questions, "That's the difference. I think that's an important lever that parents have. Either you can open it up and say, look, this and this happened. That's why that name was used. If parents become more intimate with what their children are doing, what they are learning, they might be able to change things.”

Marianne’s insights brought me back to a conversation I had with Louisa. As Marianne has highlighted, the parents must actively engage with the education of their children not only for the benefit of the child, but for the benefit of themselves too. Louisa had told me about all the work she was doing in changing the curriculum to decolonise it, which in turn would create a greater understanding of different cultures in the United Kingdom which would hopefully bleed into society making it a more tolerant environment. However when I asked the question of how we ensure these practices in school are not then undone at home, she paused. “Maybe [the answer] is schools communicating better with parents, in terms of what the vision is, and the rationale for that” Louisa told me. “Maybe getting parents in to explain the curriculum and the drive behind it. Then difficult conversations would come up, because we're there for them to question”. Both Louisa and Marianne have lead me to believe that education needs to happen throughout all demographics, not just school children. For Luca to feel comfortable to wear her Germany shirt with pride in a place full of English fans, these individuals would need to actively engage with the new forms of teaching and be open to new ideas. A goal that is perhaps easy to dismiss as a dream, the hopes lie with future generations.

“I hope what's happening is we've at least planted the seed of something that even if they go home and they hear that other opinion, because that's what we try and do in all of our lessons where you've got to question opinions all the time. You've got to question what people are saying. In this age of fake news, as well, they've got to be critical with their sources of information. So I hope that they just are instilled with the ability to have that and then as they grow older, they'll have a more tolerant view of things, and then they'll pass it on to their children.”

Louisa McKie

The teaching of Britain’s colonial past in schools is much more than a history lesson. As Louisa and Marianne have pointed out, transparency about the past can result in a more tolerant society, providing everyone is on board. Given teachings of British historical wrongdoings are fairly new, I was still fascinated by the German education system and how they approached teaching of Nazi Germany to school children in modern day. I wanted to see how the head on teachings that Marianne received had developed to a generation more disconnected from that era. I spoke to Mike Stuchberry, an educator turned journalist in Stuttgart, Germany. Mike explained to me the differences in generations in Germany, and how the education would differ: “Students or people my age, would have had it [education around Nazi German] a little bit more thickly applied than those who were born after 1990. It is taught quite sensitively. It's not a case of saying, you know, we're so bad, Germans were terrible, it's more of a look at how these tools are used in such a way to influence people.” Already I saw that what Marianne had highlighted about engaging in how and why things happened as opposed to simply stating that it happened was being applied within German schools.

If I cast my mind to my education at school, I vaguely remember studying for a topic once, taking an exam and then never revisiting it. However, Mike explains to me when it comes to Nazi Germany being taught in German schools, this is not the case: “In Germany, things are sort of jumbled up over time. So you don't do things necessarily chronologically. We look at different aspects of the Nazi era, for three years straight. That's probably the experience of most Germans born after, say, let's say 1990.”

Mike confirmed what Eva had said, that the Nazi era is very thickly applied and this can quite easily turn into a guilt complex. He goes on to explain how the past is used to reflect on society today, in order for the events of the Nazi era to never happen again: “There's more focus on the media, looking at the media, looking at Nazi publications that were around at the period and saying can you see any echoes in modern German media or modern media anywhere, and I mean, sometimes that means that the media can be a bit overly sensitive. But yeah, that's very strong.”

This method of considering the events of the past and applying them to modern day is a perfect example of learning from history. It is no secret that the Nazi’s utilised propaganda to gain a following, and schools in Germany are actively teaching their students how to notice this behaviour in order to stamp it out before it begins. But how can we in Britain apply this to our own society? As Luca expresses to me: “I was thinking there's no term you could say to an English person like that. You can't call them a coloniser. Nazi is just very like grippy and it's fast. It's a good slur, isn't it?.”

The German Womens team celebrating a 2-1 victory over Spain in Euro 2022. Video by Luca Wodtke

The German Womens team celebrating a 2-1 victory over Spain in Euro 2022. Video by Luca Wodtke

At its height in 1922, the British Empire spanned over a quarter of the earth, ruling over 458 million people. Concentration camps are something closely attributed to Germany from the second world war, and yet it seems forgotten that Britain were operating concentration camps in South Africa during the Second Boer War. 28,000 white people and 20,000 black people perished in these camps. This is one event out of many during the reign of the British Empire that claimed many lives, and various estimates claim the lives lost under the British empire range in the millions. Based on this information, if Luca were to retort back to her British abusers that they are also implicit in genocide, (as they are doing to her) would this be acceptable?

From these conversations I have gained an insight into education systems based in two countries who have committed historical atrocities. Britain is just beginning its journey into transparency and the methodology into how to teach younger generations of historic ills can take inspiration from Germany. Not afraid to confront its past, Germany has created an environment where the Nazi regime could never thrive again, and it is illegal to display Swastikas, call your child Adolf or perform a Nazi salute in public. None of these behaviours are illegal in Britain however.

I cannot help but wonder if Britain were transparent with its past, the collective guilt that Germany experiences would occur here as well. Whilst nobody should be made to feel guilty over events that took place long before their birth, this knowledge of events that Britain was involved in may create an environment where a greater understanding occurs. Luca would be free to wear her Germany shirt with pride, and without fear of being compared to a political party that committed genocide. Not only could context stop hatred, the impacts could be felt all over the country. A YouGov poll revealed that 30% of Britons believed colonies were better off as part of the British Empire. If Britain's history was truly transparent, would those polled feel the same? I can’t help but feel if a similar poll was given to the German population about their historical past, the votes would be very different indeed.

As I found with all my interviews, nobody is complicit with the horrors of the past, but that does not mean we cannot study them and build a more tolerant world as a result of them. A world where Luca doesn’t have to tell people she’s American out of fear of the responses should she say she was German. Even those alive at the time of these atrocities should not be condemned so easily, as Luca was keen for me to know. Her grandfather was given a motorcycle by the Nazi party and was then forced to work for them. Despite this, it does not make him complicit with the events that took place, as Luca tells me: “July 20th. The day they had an attempt on Hitler's life with a leather suitcase. That's my grandfather's birthday and he was the proudest person about that. So I'm saying despite him wearing a swastika on his chest. He had nothing to do with this man or these events.”

An important message. Education and context is vital to produce change, and as I think about my chat with Marianne I find myself considering the teachings of Otto Frank. Tolerance.